What Does It Matter Who Is Speaking?

“What does it matter who is speaking?” asked Michel Foucault in his famous 1969 lecture Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur?—a question which, depending on your temperament, is either thrillingly liberating or sends you scrambling back to your notes like a Victorian librarian who’s dropped his monocle.

In that question lies a fascinating problem: what happens to art when we don’t know—or aren’t allowed to know—who made it?

In this update, we’ll explore the curiosity of anonymity in art, not simply as an accidental byproduct of historical forgetfulness, but as a philosophical and psychological phenomenon through which we can examine creativity, power, perception, and the fragile edifice of cultural memory. We’ll ask why the study of anonymity matters, and how it changes the way we listen, the way we interpret, and the way we assign value. Whether the anonymity is deliberate, accidental, or imposed, it has consequences.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: the artist is not the art. Knowing that a piece was composed by Josquin or Byrd or ‘Anon.’ changes neither the dots on the page nor the vibrations in the air. And yet, for most audiences (and indeed most artists, scholars and performers) attribution exerts a powerful influence. Knowing a piece is by Josquin or Byrd predisposes us to decide that it’s going to be good before even the first note is heard. A motet of exquisite craftsmanship must, we assume, be the work of some known genius with a temporarily misplaced name-tag. It cannot simply have been—that would suggest genius is not the exclusive property of geniuses. A deeply unsettling thought.

This conflation of fame and quality is part of what psychologists call the halo effect. We assume that if someone was truly great, truly talented, truly worthy of our attention, then they must have become well known. And conversely, if they’re unknown, they probably weren’t all that special to begin with. But there’s another, deeper layer to this instinct. As Roland Barthes warned in his now-iconic essay La mort de l’auteur (1967), we are rarely content to encounter a work on its own terms. We are always tempted to ‘explain’ it through the supposed intentions of the person behind it. He therefore calls for the liberation of the text from its maker, arguing that the meaning of a work is born not at the point of writing, but at the moment of reading. Not a fixed transmission from author to audience, but a plurality of interpretations, each as valid as any other.

Sometimes, the work becomes more universal. Stripped of preconceptions and biases, it invites a perception not of what it says about its creator, but what it says to us. Other times, it becomes uncanny, more abstract, less situated, harder to love. Some may call this liberation; others may call it epistemological vertigo.

Foucault, responding in 1969, agreed in spirit but asked a different question: If authorship is dispensable, why do we keep insisting on its authority? Why does it still matter who made something? His answer was the concept of the “author-function” - not the author as person, but the author as a cultural mechanism. A name that assigns ownership, authority, legitimacy, blame. A filtering device. Or, more cynically, a branding exercise.

In 2024, an experiment by Hannah Kaube and Rasha Abdel Rahman explored just how strongly attribution influences perception. Participants were asked to evaluate works of visual art, sometimes accompanied by positive or neutral biographies about the artist, and other times by negative or controversial ones. The results were clear: participants judged the artworks less favourably when they believed the artist to have a troubling backstory, even when the images were identical. This is a triumph of context over content. Or, less charitably, proof that we are easily hypnotised by the reputational echo chamber. Anonymity cuts through that fog. By removing the name, we remove the halo. There’s no authorised reading, no pre-approved context. The hierarchy between the audience and the work is dissolved, and the encounter democratised. Rather than asking what the artist meant, we are compelled to ask: what does this mean to me?

Resisting the Urge to Solve the Riddle

Humans are compulsive pattern-finders. Faced with the unknown, we invent narratives to fill the gaps. In the case of anonymous art, this often takes the form of attribution fantasies. “It sounds Franco-Flemish, doesn’t it?” or “This must be a student of Titian.” We sniff out stylistic clues, try to match style to school, speculate about character, intention, ideology. We want someone to blame. Or to praise. Or at least someone to Google.

It’s rarely long before we’ve constructed a plausible lineage, an imaginary pupil of this or that maestro, trained in such-and-such a chapel. But in doing this, we risk replacing mystery with myth. Attribution becomes a kind of comfort blanket—a way of making the unknowable seem knowable. It’s not inherently wrong to speculate. But when we rush to fill the void, we may fail to listen to what the void itself is telling us.

Anonymity by choice, or by force.

Some artists have embraced anonymity as an aesthetic or ethical gesture. Medieval monastics, whose humility forbade self-promotion. The composer of the Gioiello Artificioso, who simply signed himself “a devout and pious follower of St Francis.” Or more recently as a political act, as with the feminist collective ‘the Guerrilla Girls’, or as a game of mystification, as with Banksy and Daft Punk. For these artists, anonymity its an artistic statement: a rejection of commodification and lionisation, a refusal to play by the market’s rules, or a critique of the cult of personality.

But let’s not get too romantic. For every artist who chose anonymity, there are many more upon whom it was imposed. Women whose works were attributed to husbands. Queer or heretical composers whose names were scratched from manuscripts. People too poor to afford publication, too far from the centres of power to enter the networks of prestige, or simply caught on the wrong side of agreeable politics, race, or religion.

This is where Foucault becomes especially urgent. In Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur?, he notes that the “author-function” only emerges in societies where authorship becomes a site of power, and to have your name remembered is to be recognised as a ‘legitimate producer of culture.’ But those systems are historically contingent, and often cruelly narrow in scope. Anonymity in this light becomes a record of exclusion and marginalisation; the void left by the gatekeepers who decided whose names ‘count’ and whose don’t.

Why Does It Matter?

First, because it reminds us that greatness often goes unsigned. The inherited lists of “Great Composers,” “Important Artists,” and “Top 10 People You’re Supposed to Care About” are full of blind spots. Anonymous music tells us there is more than we were told. It encourages us not to discard the canon, but to expand it, to define greatness more generously.

Secondly, because it asks us to confront our own habits of artistic interpretation. It tests our ability to respond to the work itself, without leaning on celebrity, reputation, or what Edward T. Cone called “the composer’s voice.” We are left to make our interpretative decisions from the inside out. What is the music doing? What is it asking for? What kind of world does it conjure, and how do we inhabit that world with care and integrity?

Thirdly, because it forces us to reckon with historical justice. And perhaps growing more attuned to these historical silences, we sharpen our eyes to the exclusions of our own time. Who gets commissioned? Who gets published? Who gets reviewed? Who are we not hearing? Whose names are being written out of future histories, even now?

And finally, if you’ll allow a moment of existential flair, anonymity brings us face to face with the contingency of all identity. It exposes how we as humans treat attribution: the assumptions we make, the value we confer, the power we give to names. It shows us how dependent we are on knowing who is speaking before we decide whether to listen.

So yes, it matters. Not because anonymity is a riddle to be solved, or a gimmick to be exploited — but because it is a condition that asks something of us.

And let’s be honest. Sometimes it’s a relief not to have to pretend we care about the composer’s personal trauma, which archduke they were trying to impress, or how many extramarital affairs they had in Florence, before we can enjoy the work.

Further Reading

If Barthes and Foucault are the patron saints of postmodern anonymity, there are many others worth inviting to the dinner party. Judith Butler’s work on performativity could be marshalled to understand anonymity as a gendered mark. Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste explains why known names accumulate cultural capital, while the anonymous remain invisible. In a world where taste is shaped by prestige, no name means no currency. Contemporary neuropsychologist Paul Bloom explains in How Pleasure Works that our aesthetic judgments are shaped more by backstory than by sensory input. The wine tastes better because we think it’s expensive, Bloom would claim. Kwame Anthony Appiah is an essential companion to Foucault’s ideas of identity as a construct within a closed system and that someone whose name was never preserved may never have been admitted to that network in the first place. We might also include Levinas on the ethical encounter with the unknown, Derrida on the instability of authorship, or Tia DeNora on music as social practice.

But perhaps that’s enough for now. The dinner party is getting a little tense, and someone is about to bring up Schoenberg.

Anon.

June 2025

From Discovery to Performance: A ‘Behind the Scenes’ Look at ANON’s Editing Process

If you’ve ever wondered how a motet long buried in the back of a Renaissance choirbook ends up on one of ANON’s concert programmes, the answer is: slowly, painstakingly, and with lots of squinting.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at how we take forgotten music from silent manuscript to living performance.

Step one – The Hunt Begins

We start with the libraries. If a major European library has a large choral collection, we’ve probably been through it. Many institutions have digitised their holdings, for which we’re immensely grateful. But some have not, in which case a politely worded email to a curator or librarian can sometimes conjure up an unlisted facsimile or even a dusty old microfiche. (Microfiche, for our Gen Z readers, is like a PDF but worse in every single way.)

Step two – But is it really anonymous?

Just because a piece is anonymous in one source doesn’t mean it’s anonymous everywhere. This is where the cross-referencing begins. We consult library catalogues, RISM, DIAMM, the Polyphony Database, IMSLP, articles, studies, theses, bibliographies, and even CPDL when we must. These help us determine whether the piece exists elsewhere, and whether a composer’s name has ever been attached to it.

Step three – Piecing it together

Once we’ve ruled out known attributions and built a working picture of when and where the piece might have been composed, we try to identify all surviving concordances. This can get complicated. Renaissance manuscripts often scatter voice parts across different books, and you don’t always know how many parts you’re looking for. Four? Five? Twenty?

Sometimes it becomes clear that a partbook is missing completely, or that a voice drops out halfway through. At this point we either keep digging or reluctantly let the piece return to its slumber.

Step four – The First Glimpse

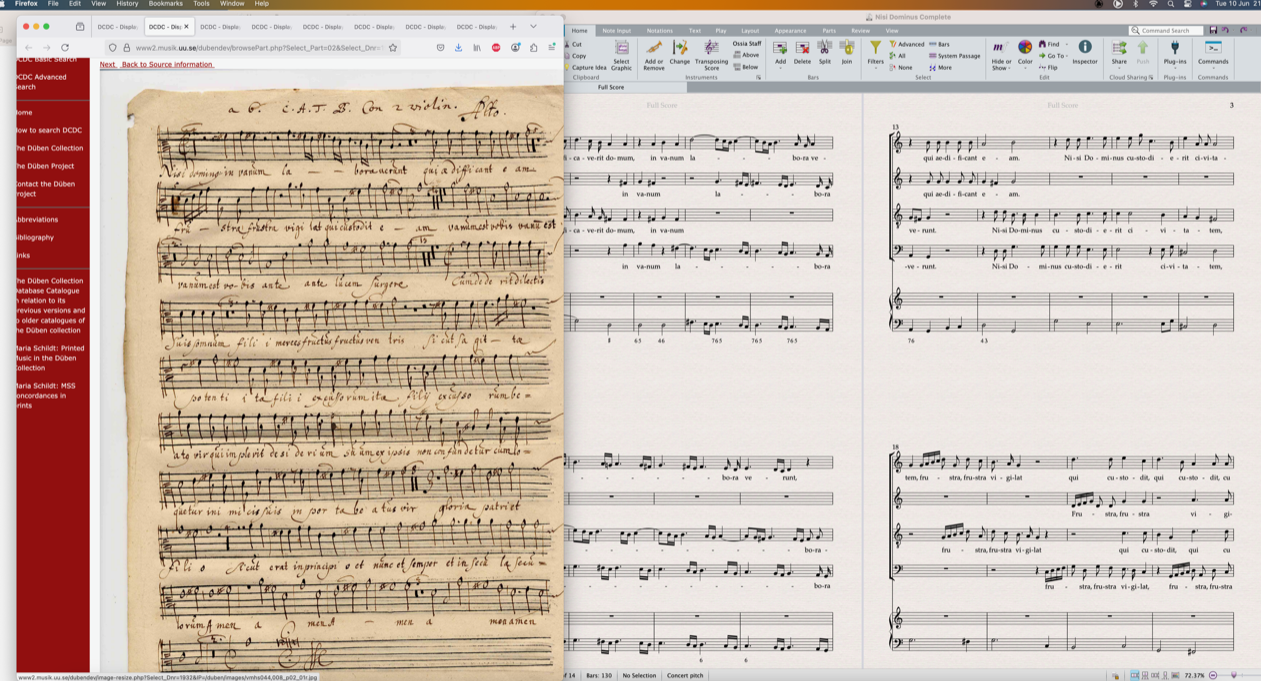

If all the parts are present, intact and legible, we start transcribing the music into modern editing software. ANON uses Sibelius, but there are many options available to suit a range of preferred uses and budgets. We typically begin with he first 20 or 30 bars – just enough to determine whether the piece is a hidden gem or a well-meaning failure.

Some pieces are heartbreakingly beautiful. Others are heartbreakingly awful. We’ve found some exceptionally exquisite pieces, but also our fair share of derivative, dull, harmonically inert pieces, and works so formulaic that even the scribe appears to have lost interest halfway through. Sometimes it’s no wonder the composers didn’t want to attach their name to the pieces. These we quietly set aside.

Step five – Making an Edition

If the piece holds promise, we make a usable edition. ANON’s editions are intentionally light on editorial markings – we aim for a balance between historical integrity and modern practicality. We apply editorial judgement where needed, but avoid imposing too much modernity. However, all our editions are intended to be performed, as well as studied, and so we do make interventions where clarity and utility demand it. So far, we’ve assembled a collection of over 1,000 such pieces, many (if not most) of which haven’t been heard for centuries.

Step six – Tag, Sort, Organise

Once edited, each piece is catalogued and tagged with metadata: Likely date, voicing, text source, stylistic traits, liturgical function, and so on. This helps us group pieces together thematically. A few of the concert themes currently in the pipeline are:

- Vespers: The usual liturgical structure of vespers, with a ‘Venetian’ slant. Includes pieces for organ and soloists with continuo.

- Quem Vidistis?: Anonymous advent and Christmas motets and carols, some medieval.

- The Five Sorrowful Mysteries: A dramatic journey from Gethsemane to Calvary.

- The Artificial Jewell: Madrigals, secular canzone, parody masses and magnificats based on madrigals. Some instrumental pieces.

- Song of Songs: Everyone’s favourite biblical erotic poetry disguised as sacred allegory.

- Nocturn: Based on the ‘forgotten’ liturgical hours. Candlelit and moody.

- The Seven Sorrows of Mary: Marian antiphons and motets based on the seven sorrows, interspersed with anonymous poetry.

And many more. The possibilities are endless, and the more we discover, the more obvious it is that our journey has just begun.

Step seven

Finally, the piece enters rehearsal, and is tested against the human voice. We sing it, tweak our edition where needed, and gradually bring the music back to life. Some pieces take flight immediately. Others take a bit of coaxing. But this is also the most rewarding stage. It’s where the work stops being a puzzle and becomes music again. A living, breathing thing. Something you can hear, not just read.

Every ANON concert includes music that has been through this process: found, investigated, cross-referenced, deciphered, judged, edited, rehearsed, and revived. It’s a lot of work, but worth every moment. Because after all, a piece of music isn’t truly anonymous until nobody performs it.

Two Pieces in Focus

We want to take a moment to share two of the extraordinary works that ANON is currently bringing back to life—pieces that speak not only through their beauty, but through the silences surrounding them, Domine Adauge Nobis Fidem and a setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah.

Domine Adauge Nobis Fidem (c.1560), comes from a manuscript now held in the Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. A work of rare compositional sophistication, this hymn is written for eight voices in two choirs which are in perfect canon. A curious hand-written note in the margin claims:

“This song was brought from Prussia. It is unknown whether the composer is black or white.”

We suspect that this enigmatic comment is not, in fact, speculation as to the race of the composer, but rather an archaic way of saying that the writer of the note knows absolutely nothing about them, in the same way that it might be said ‘I don’t know them from Adam’. We may never know who wrote this music. But the question left hanging in the margins is a reminder of how little history has preserved about those working outside accepted norms of identity, geography, or power.

O Domine, adauge nobis fidem,

succurre in credulitati nostrae.

Dicit enim Dominus Jesus Christus:

omnia possibilia sunt credenti.

Adauge nobis fidem,

succurre in credulitati nostrae.

O Lord, increase our faith;

help our unbelief.

For the Lord Jesus Christ says:

all things are possible to those who believe.

Increase our faith;

help our unbelief.

The Book of Lamentations is a series of poetic writings from the Old Testament, attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, mourning the destruction of Jerusalem following its siege by the Babylonians in 587 BC. These mournful verses express sorrow, loss, and the longing for restoration, often interpreted as a symbol of hope amidst suffering and despair. They have spoken across the centuries, particularly in times of persecution and exile. Throughout history many composers have set this text to music, including a composer very familiar to ANON’s Lincoln singers, William Byrd. Something unique about Byrd’s setting of this text is how he modified the text making it unsuitable for use in Roman or Sarum liturgy. In the private library of Sir John Lumley, now held in the British Library, ANON have found another setting of the Lamentations, likely written around 1570 by, of course, an anonymous composer. Like Byrd’s, this setting may have been used in secret Catholic gatherings at the height of Elizabethan persecution, when English Catholics, like Jeremiah, mourned the destruction of their own holy city: the Catholic Church. With this in mind, it is highly likely that the composer of the anonymous lamentations intentionally left their name off the work, to protect themselves from persecution in case the music was discovered. However, there is one particular clue as to the identity of this composer. The anonymous ‘Lumley Lamentations’ possess the same idiosyncrasies in the text as Byrd’s own setting. Whether this is a complete coincidence, someone whose name has been lost to time imitating or inspiring Byrd, or a long lost piece by Byrd himself, we will probably never know, but that does not mean that the music deserves to be forgotten.

These are the kinds of pieces ANON is here to rediscover and share—not just musical curiosities, but deeply human expressions of longing, resilience, and faith. Voices that once rang out in exile, or in hiding, or far from home.